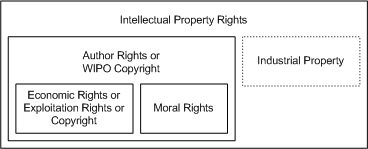

In the specification, we are going to analyse the subject domain, i.e. copyright. First of all, it is situated in the broader context of intellectual property (IP) at the international level, which is defined by the international agreements managed by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). This section shows that IP is divided into industrial property and copyright. As our intention is to deal with literary, artistic and scientific works, the focus is going to be placed on the latter part.

We will not deal with inventions, which are, on the contrary to scientific discoveries, basically technical. Patents govern them. We will not deal with trademarks and industrial designs either. Therefore, we are going to deal just with copyright. It is important to note that we understand copyright from the wider definition hold by the WIPO. Traditionally, copyright has been associated with just the economic rights, also know as exploitation rights. This is common in Anglo-Saxon legal traditions like those in the United Kingdom or the USA. However, in addition to economic rights, and as WIPO does, we are also considering moral rights.

Once the focus is placed on copyright, this specification concentrates on the analysis of its main concepts. First, the concept of “Work” is detailed. What are considered works? What requirements must be satisfied in order to have a copyrighted work? What kinds of copyrighted works are there? Then, copyright is divided into the different rights that compose it. They govern very specific kinds of actions that can be carried out on works. The rights related to copyright are also described, i.e. those corresponding to performers, producers and broadcasters. To conclude, the limitations and exceptions of copyright are shown.

Intellectual property, very broadly, means the legal rights that result from intellectual activity in the industrial, scientific, literary and artistic fields. Intellectual property includes rights related to:

Literary, artistic and scientific works.

Performances of performing artists, phonograms and broadcasts.

Inventions in all fields of human endeavour.

Industrial designs.

Trademarks, service marks, commercial names and designations.

Countries have laws to protect intellectual property for two main reasons. One is to give statutory expression to the moral and economic rights of creators in their creations and the rights of the public in access to those creations. The second is to promote, as a deliberate act of Government policy, creativity and the dissemination and application of its results and to encourage fair-trading, which would contribute to economic and social development.

Generally speaking, intellectual property law aims at safeguarding creators and other producers of intellectual goods and services by granting them certain time-limited rights to control the use made of their productions. Those rights do not apply to the physical object in which the creation may be embodied but instead to the intellectual creation as such.

Intellectual property is traditionally divided into two categories [WIPO04]:

Industrial property, which includes inventions (patents), trademarks, industrial designs, and geographic indications of source.

Copyright, which includes literary and artistic works such as novels, poems and plays, films, musical works, artistic works such as drawings, paintings, photographs and sculptures, and architectural designs. Rights related to copyright include those of performing artists in their performances, producers of phonograms in their recordings, and those of broadcasters in their radio and television programs.

Industrial property covers inventions and industrial designs. Simply stated, inventions are new solutions to technical problems and industrial designs are aesthetic creations determining the appearance of industrial products. In addition, industrial property includes trademarks, service marks, commercial names and designations, including indications of source and appellations of origin, and protection against unfair competition. Here, the aspect of intellectual creations is less prominent, but what counts here is that the object of industrial property typically consists of signs transmitting information to consumers, in particular as regards products and services offered on the market, and that the protection is directed against unauthorized use of such signs which is likely to mislead consumers, and misleading practices in general.

On the other hand, copyright, as understood by the WIPO deals with all the aspects of literary, artistic and scientific works we are interested in, i.e. their economic exploitation but also the moral rights of the author. Traditionally, copyright has been associated with just the economic rights, also know as exploitation rights. Another term that we will also use to refer to the union of economic and moral rights is author rights. This is the more concrete term although it is common just in continental Europe legal tradition.

The WIPO is promoting the introduction of moral rights in all legal systems in order to harmonise Intellectual Property worldwide and the WIPO definition of copyright does already include them. Therefore, copyright is the focus of this work and is analysed in the next section with greater detail. Figure shows a summary of all these terms and how they are related to more general terms.

Copyright law is a branch of that part of the law that deals with the rights of intellectual creators [Bercovitz03]. Copyright law deals with particular forms of creativity, concerned primarily with mass communication. It is concerned also with virtually all forms and methods of public communication, not only printed publications but also such matters as sound and television broadcasting, films for public exhibition in cinemas, etc. and even computerized systems for the storage and retrieval of information.

Copyright deals with the rights of intellectual creators in their creation. Most works, for example books, paintings or drawings, exist only once they are embodied in a physical object. But some of them exist without embodiment in a physical object. For example music or poems are works even if they are not, or even before they are, written down by a musical notation or words. However, there are some legal systems that do not protect the copyright of works that have not been fixed in some form.

Copyright law protects only the form of expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves. The creativity protected by copyright law is creativity in the choice and arrangement of words, musical notes, colours, shapes and so on. Copyright law protects the owner of rights in artistic works against those who take and use the form in which the original work was expressed by the author.

At the international level, the Berne Convention confers the economic and moral rights for the protection of literary and artistic works, commonly known as the Berne Convention. This Convention, which was adopted in 1886, has been revised several times to take into account the impact of new technology on the level of protection that it provides. It is administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), one of the specialized international agencies of the United Nations system. The Treaties section contains a full list of all the international regulations managed by the WIPO.

Legislation provides protection not only for creators of intellectual works but also for the auxiliaries that help in the dissemination of such works. This auxiliaries protected by legislation are performers, producers and broadcasters. The owner of copyright in a work is generally, at least in the first instance, the person who created the work, that is to say, the author of the work. There can be exceptions to this general principle and national laws regulate such exceptions. For example, some national laws provide that, when a work an author employed for the purpose of creating that work, then the employer, not the author, is the owner of the copyright in the work.

From this initial situation, copyright, with the exception of moral rights, may be assigned. This means that the owner of the copyright transfers it to another person or entity, which becomes the owner of the copyright. In some other countries, an assignment of copyright is not legally possible. However, licensing achieves almost the same practical effect than assignment.

Licensing means that the owner of the copyright remains the owner but authorizes someone else to exercise all or some of his rights, usually subject to some limitations. When such authorization or license extends to the full period of copyright and when such authorization or license extends to all the rights, the licensee is for all practical purposes in the same position as an owner of copyright. However, this is just from the economic rights point of view. Moral rights cannot be licensed neither be transferred.

The subject matter of copyright protection includes every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever the mode or form of expression. For a work to enjoy copyright protection, however, it must be an original creation. The ideas in the work do not need to be new but the form, literary or artistic, in which they are expressed, must be an original creation of the author. And, finally, protection is independent of the quality or the value attaching to the work. It will be protected whether it be considered, according to taste, a good or a bad literary or musical work and even of the purpose for which it is intended, because the use to which a work may be put has nothing to do with its protection.

Works eligible for copyright protection are, as a rule, all original intellectual creations. A non-exhaustive, illustrative enumeration of these is contained in national copyright laws. To be protected by copyright law, an author's works must originate from him; they must have their origin in the labour of the author. But it is not necessary, to qualify for copyright protection, that works should pass a test of imaginativeness, of inventiveness. The work is protected irrespective of the quality thereof and also when it has little in common with literature, art or science, such as purely technical guides or engineering drawings, or even maps. Exceptions to the general rule are made in copyright laws by specific enumeration; thus laws and official decisions or mere news of the day are generally excluded from copyright protection.

Practically all copyright law systems provide for the protection of the following types of work:

Literary works: novels, short stories, poems, dramatic works and any other writings, irrespective of their content (fiction or non-fiction), length, purpose (amusement, education, information, advertisement, propaganda, etc.), form (handwritten, typed, printed; book, pamphlet, single sheet, newspaper, magazine); whether published or unpublished; in most countries “oral works”, that is, works not reduced to writing, are also protected by the copyright law.

Musical works: whether serious or light; songs, choruses, operas, musicals, operettas; if for instructions, whether for one instrument (solos), a few instruments (sonatas, chamber music, etc.), or many (bands, orchestras).

Dramatic, pantomimes and choreographic works: including any accompanying music.

Artistic works: whether two-dimensional (drawings, paintings, etchings, lithographs, etc.) or three-dimensional (sculptures, architectural works), irrespective of content (representational or abstract) and destination (“pure” art, for advertisement, etc.);

Maps, technical drawings and architectural works.

Photographic works: irrespective of the subject matter (portraits, landscapes, current events, etc.) and the purpose for which they are made.

Motion pictures: whether silent or with a soundtrack, and irrespective of their purpose (theatrical exhibition, television broadcasting, etc.), their genre (film dramas, documentaries, newsreels, etc.), length, method employed (filming “live,” cartoons, etc.), or technical process used (pictures on transparent film, videotapes, DVDs, etc.).

Computer programs: either as a literary work or independently depending on the concrete legal system.

Please note that mere ownership of the material support of a copyrighted work, i.e. a Compact Disc or a painting, does not give you the automatic right to copy part or all of that work. If you are not the copyright holder, you are ordinarily limited to making one archival copy (reserved for your own use in case the original becomes damaged). Even where you make the outright purchase of an original work of art, the original artist may retain certain rights in the manner in which the artwork is displayed, and may through a contract of sale retain the right to reproduce the work ownership of the original work alone will not necessarily entitle you to make or sell copies.

As it has been said, the first requirement in order to be a copyrighted work is originality, which is detailed below. Moreover, there are some kinds of works that are not subject to copyright:

A part from these conditions, in some countries there is also the need for the work to be fixed in some way in order to be protected. No other actions are required for copyright protection. There is no need to file an application for copyright protection, or to even place a copyright notice on a work. These additional steps, often referred to as "formalities", were previously required to secure copyright protection. Under the current law, the formalities of registration and notice now merely serve as recommended steps to expand the protection provided by copyright.

For a work to be protected by copyright law, it must be "original". The ideas in the work do not need to be new but the form, literary or artistic, in which they are expressed, must be an original creation of the author. However, the amount of originality required is extremely small. The work cannot be a mere mechanical reproduction of a previous work, nor can the work consist of only a few words or a short phrase. In addition, if the work is a compilation, the compilation must involve some originality beyond mere alphabetic sorting of all available works. Beyond that, almost any work that is created by an author will meet the originality requirement, although it might be considered a derivation from a previous work.

The author of the work must be a human being. The works performed by machines are not protected. In these cases, what is protected instead is the mechanism or procedure that generates the work. For instance, a computer program, which generates drawings, music or translations, will be protected by copyright and the works that it generates will not. Photos are also produced by machines, however what is valued in this case is the contribution of the photographer in order to choose the framing, exposure, etc.

The definition of originality is another important point. Usually, it is understood subjectively, i.e. the work is original in the sense that it is not a copy of a previous work and at least can be considered a derivation as it contributes some original work. On the contrary, objective originality, i.e. to create something new, is usually employed in the patents domain. Moreover the level of originality required is dependent on the field of the contribution. For instance there is not the same originality requirement for major works, like books or songs, than for minor works, like flyers or slogans. Correspondingly, the level of protection against similar creations depends on the creativity contribution of the work. When the contribution is small it is easier that similar works are considered distinct works.

In some countries, works that have not been fixed in a tangible form of expression are not subject to copyright. For example, a poem, a dance work that has never been notated or recorded or a speech or performance that was not written and was not recorded, may not be subject to copyright.

For instance the U.S.A. as stated in the U.S. Copyright Act, in order for a work to be protectable, it must be fixed in a tangible medium of expression. A work is considered fixed when it is stored on some medium in which it can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated. For example, a song is considered fixed when it is written down on paper. The paper is the medium on which the song can be perceived, reproduced and communicated.

It is not necessary that the medium be such that a human can directly perceive the work from it, as long as a machine can perceive the work. Thus, the song is also fixed the moment the author records it onto a cassette tape. Similarly, a computer program is fixed when stored on a computer hard drive. In fact, courts have even held that a computer program is fixed when it exists in the RAM of a computer. This is true even though this "fixation" is temporary, and will disappear once power is removed from the computer.

However, this is not the general case. There are other countries that extend copyright protection to unfixed works, e.g. poems, music, dance works, speeches, etc. In any case, it is very complicated to protect a work that has never been fixed. It is very difficult to demonstrate authorship if there is not material evidence.

From the moment an original work is fixed in a tangible medium of expression, copyright applies whether or not there is a notice of copyright affixed to the work. A created work is considered protected by copyright as soon as it exists. According to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, literary and artistic works are protected without any formalities in the countries party to that Convention. Thus, WIPO does not offer any kind of copyright registration system.

However, a copyright notice helps protect an original work by protecting against a claim of innocent infringement, and by helping people who wish to license the work to find and contact the author. The notice should be affixed in such a way as to give reasonable notice of the claim of copyright. A proper copyright notice includes three elements:

In order to maximize your protections under international conventions, you should always utilize the symbol © in your copyright notices (or the symbol for sound recordings), and should also include the phrase: "All rights reserved". For example: "© 2005 Roberto García González, All Rights Reserved".

Moreover, many countries have a national copyright office and some national laws allow for registration of works for the purposes of, for example, identifying and distinguishing titles of works. In certain countries, registration can also serve as evidence in a court of law with reference to disputes relating to copyright.

A compilation is a work that is formed by the collection and assembling of pre-existing materials or of data (databases) that are selected in such a way that the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship. An example of a compilation would be a collection of the most influential plays of the Eighteenth Century. The individual plays themselves would not be subject to copyright protection, since the copyright would have expired. However, the selection of the plays, as well as their order, involves enough original and creative expression to be protected by copyright. Therefore, the grouping of plays is protected by the copyright in the compilation even though each individual play is not protected.

A grouping of facts is also protected as a compilation, assuming the grouping contains enough original expression to merit protection. An example of a protectable grouping of facts would be a web site containing links to other web sites. Each link consists merely of factual information, namely that a particular web site can be found at a particular URL location. Thus, there is no copyright protection for the links. Although the individual links can be copied and placed unto another web site, if the entire list (or a substantial portion) of the list were copied, the copyright in the compilation would be infringed. The creative, original expression that is being protected is the sorting, selecting, and grouping of all the selected web sites into the list found on this web page.

The white pages telephone directory is an example of an unprotected grouping of facts. The individual facts (name, address, and telephone number) are not protectable under the copyright law. In addition, the compilation in this case consisted solely of gathering all available telephone numbers in a particular area and sorting them alphabetically. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that this minimal level of selecting and arrangement does not involve enough originality to be protected by copyright.

The initiative to create a collective work is carried out by a special individual. This individual, a juridical or natural person, also coordinates the creative process, divulgates the work and usually finances it. This person is considered the author with all the corresponding rights. The work is built from the contributions of different authors, who are coordinated by the promoter, which are combined in a unique an autonomous work.

Copyright in each separate contribution to a collective work is distinct from copyright in the collective work as a whole, which is held by author of the contribution. In the absence of an express transfer of the copyright or of any rights under it, the owner of copyright in the collective work is presumed to have acquired only the privilege of reproducing and distributing the contribution as part of that particular collective work, any revision of that collective work, and any later collective work in the same series.

In the case of works made for hire, where an artist has created the work as an employee, the employer, and not the employee, is considered to be the author and copyright holder.

Two or more authors, who collaborate directly or indirectly, create a collaborative work. They will share the copyright on the resulting work unless there is an agreement to the contrary.

This kind of works is based in pre-existent ones without the collaboration of their original authors. Their rights must be considered and their authorisation is required. Derivations, although based in previous ones, must be original as any other work, i.e. they contribute something and a new work can be identified. If the changes are not substantial, the result is a reproduction.

New derivation is dependent on the pre-existent work because it maintains some of their characteristic features. This is different to say that a work is inspired in previous works, which happens always consciously or not and does not have legal implications. Inspiration, like ideas, is totally free.

Therefore, the originality of derivations is based on the adaptation of an original work or its translation to a different language. Examples of derivations are: the adaptation of a dramatic work to novel or the translation of a film. The adaptation of a literary work to music is not considered derivation, it is considered inspiration.

The author of a derived work enjoys the same rights than any other author while the rights situation of the original work is not affected in any way. The rights holder of the latter may continue authorising transformations while they are also original with regard to other previously derived works.

However, in order to realise and commercially exploit the derived work an authorisation of the original rights holder is required. Moreover, there might be a chain of derivations that implies a chain of authorisations from the rights holders of the preceding works each time a new derivation is intended. This means that the authorisation to transform a work and to exploit the derived work does not imply the consent to new transformations from the derived work. The full chain of authorisations must be followed.

The owner of copyright in a protected work may use the work as he wishes, but not without regard to the legally recognized rights and interests of others, and may exclude others from using it without his authorization.

Therefore, the rights bestowed by law on the owner of copyright in a protected work are frequently described as exclusive rights to authorize others to use the protected work. The original authors of works protected by copyright also have moral rights, in addition to their exclusive rights of an economic character.

What is meant by using a work protected by copyright? Most copyright laws define the acts in relation to a work which cannot be performed by persons other than the copyright owner without the authorization of the copyright owner. Such acts, requiring the authorization of the copyright owner, normally are like the following:

Specific rights in copyright govern these acts. They are shown as groups of related rights in Figure and detailed in the next subsections.

The right of the owner of copyright to prevent others from making copies of his works is the most basic right under copyright. For example, the making of copies of a protected work is the act performed by a publisher who wishes to distribute copies of a text-based work to the public, whether in the form of printed copies or digital media such as CD-ROMs. Likewise, the right of a phonogram producer to manufacture and distribute compact discs (CDs) containing recorded performances of musical works is based, in part, on the authorization given by the composers of such works to reproduce their compositions in the recording. Therefore, the right to control the act of reproduction is the legal basis for many forms of exploitation of protected works.

Other rights are recognized in national laws in order to ensure that the basic right of reproduction is respected. They are related to the exploitation of the resulting copies by distributing them to the public, renting them or importing them.

This right authorises the distribution to the public of previously made copies of works incorporated in a tangible article. The right of distribution is usually subject to exhaustion upon first sale or other transfer of ownership of a particular copy. This means that, after the copyright owner has sold or otherwise transferred ownership of a particular copy of a work, the owner of that copy may dispose of it without the copyright owner's further permission, for example, by giving it away or even by reselling it.

The right to authorize rental of copies of works is justified because technological advances have made it very easy to copy these types of works. Experience in some countries has shown that copies were made by customers of rental shops, and therefore, that the right to control rental practices was necessary in order to prevent abuse of the copyright owner's right of reproduction.

Some copyright laws include a right to control importation of copies as a means of preventing erosion of the principle of territoriality of copyright. This is because the legitimate economic interests of the copyright owner would be endangered if he could not exercise the rights of reproduction and distribution on a territorial basis. It is important to note that, despite of globalisation and digitalisation, this has still meaning as reproduction right and its related rights refer to tangible copies of works.

Another act requiring authorization is the act of public performance. To perform a work means to recite, render, play, dance, or act it, either directly or by means of any device or process or, in the case of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to show its images in any sequence or to make the sounds accompanying it audible. This right just considers public performances, i.e. performances before an audience.

It is important to note that the performance is considered public when it takes place at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is involved. Therefore, it will not be considered public when it is performed in a strictly domestic domain.

The right to control this act of public performance is of interest not only to the owners of copyright in works originally designed for public performance, but when others may wish to arrange the public performance of works originally just intended to be used by being reproduced and published.

Examples of public performances are:

A work is considered fixed when it is stored on some medium in which it can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated. For example, a song is considered fixed when it is written down on paper. The paper is the medium on which the song can be perceived, reproduced and communicated. It is not necessary that the medium be such that a human can perceive the work, as long as the work can be perceived by a machine. Thus, the song is also fixed the moment the author records it onto a cassette tape. Similarly, a computer program is fixed when stored on a computer hard drive.

This is the right that governs the act of making a sound recording of a work protected by copyright. Sound recordings can incorporate music alone, words alone or both music and words. The right to authorize the making of a sound recording belongs to the owner of the copyright in the music and also to the owner of the copyright in the words. If the two owners are different, then, in the case of a sound recording incorporating both music and words, the maker of the sound recording must obtain the authorization of both owners. Under the laws of some countries, the maker of a sound recording must also obtain the authorization of the performers who play the music and who sing or recite the words.

A motion picture is a visual recording, giving to viewers an impression of motion. In the technical language of copyright law it is often called a cinematographic work or an audiovisual work. A drama originally written for performance by performers to an immediately present audience, i.e. a live performance can be visually recorded and shown to audiences far larger in numbers than those who can be present at the live performance. Such audiences can see the motion picture far away from the place of live performance and at times much later than the live performance.

This is the right to authorize any communication to the public of the originals or copies of works, including wire or wireless means and "the making available to the public of works in a way that the members of the public may access the work from a place and at a time individually chosen by them". The quoted expression covers in particular on-demand, interactive communication through the Internet. This right just covers all communication to the public not present at the place where the communication originates. This right should cover any such transmission or retransmission of a work to the public by wire or wireless means, including broadcasting.

When a work is broadcasted, a wireless signal is emitted into the air, which can be received by any person, within range of the signal, who possesses the equipment (radio or television receiver) necessary to convert the signal into sounds or sounds and images. When a work is communicated to the public by cable, a signal is diffused and only persons who possess the required equipment linked to the cables used to diffuse the signal can receive it.

The broadcasting and diffusion by cable of works protected by copyright have given rise to new problems resulting from technological advances, which have introduced changes in copyright law. The advances include the use of space satellites to extend the range of wireless signals, the increasing possibilities of linking radio and television receivers to signals diffused by cable, and the increasing use of equipment able to record sound and visual images, which are broadcast or diffused by cable. This has originated the creation of a related right associated to broadcasters, which is detailed in the Related Rights section.

Due to recent technological advances, among which the Internet is the more relevant one, copyright has also included a particular kind of communication where members of the public access works from a place and at a time individually chosen by them. This kind of actions, i.e. interactive on-demand transmissions, is common in recent communication mediums like the Internet or mobile communications networks.

The acts of translating or of adapting a work protected by copyright require the authorization of the copyright owner. Translations and adaptations are themselves works protected by copyright. Therefore, in order, for example, to reproduce and publish a translation or adaptation, the publisher must have the authorization both of the owner of the copyright in the original work and of the owner of copyright in the translation or adaptation.

Moreover, there can be chains of transformations that force a chain of authorisations from the owner of the copyright of the original work through all transformed works until the current transformation.

To translate means the expression of a work in a language other than that of the original version.

To Adapt is generally understood as the modification of a work from one type of work to another, for example adapting a novel so as to make a motion picture, or the modification of a work so as to make it suitable for different conditions of exploitation, for example adapting an instructional textbook originally prepared for higher education into an instructional textbook intended for students at a lower level.

The Berne Convention requires member countries to grant to authors:

These rights, which are generally known as the moral rights of authors, are required to be independent of the usual economic rights and to remain with the author even after he has transferred his economic rights.

There are countries where additional moral rights are also considered:

There exist rights related to, or "neighbouring on", copyright. These rights are generally referred to as "related rights" or "neighbouring rights" in an abbreviated expression. It is generally understood that there are three kinds of related rights:

Protection of those who assist intellectual creators to communicate their message and to disseminate their works to the public at large is attempted by means of related rights. A play needs to be presented on the stage; a song needs to be performed by artists, reproduced in the form of records or broadcast by means of radio facilities. All persons who make use of literary, artistic or scientific works in order to make them publicly accessible to others require their own protection against the illegal use of their contributions in the process of communicating the work to the public.

Several countries also grant a sort of moral right to performers to protect them against distortion of their performances and grant them the right to claim the mention of their name in connection with their performances. Some countries also protect the interests of broadcasting organizations by preventing the distribution on or from their territory of any program-carrying signal emitted to or passing through a satellite, by a distributor for whom the signal is not intended.

A publisher reproduces a manuscript in its final form without adding to the expression of the work as created by the author. The interests of book publishers are protected by means of copyright itself. The position is slightly different with regard to dramatic and musical works, pantomimes, or other types of creative works intended for either audiovisual reception. Where some of such works are communicated to the public, they are produced or performed or recited with the aid of performers. In such cases, there arises the interest of the performers themselves in relation to the use of their individual interpretation in the performed work.

The problem in regard to this category of intermediaries has become more acute with rapid technological developments. Where, at the very beginning of the 20th century, the performance of dramatists, actors, or musicians ended with the play or concert in which they performed, it is no longer so with the advent of the phonograph, the radio, the motion picture, the television, satellites, etc.

These technological developments made possible the fixing of performances on a variety of material, e.g. records, cassettes, tapes, films, etc. What was earlier a localized and immediate phase of a performance in a hall before a limited audience became an increasingly permanent manifestation capable of unlimited and repeated reproduction and use before an equally unlimited audience that went beyond national frontiers. The development of broadcasting and more recently, television, also had similar effects. These technological innovations have made it possible to reproduce individual performances by performing artists and to use them without their presence and without the users being obliged to reach an agreement with them.

In order to make this situation more fair for performers, the WIPO promoted the Rome Convention as a mean to incorporate new instruments in the legal systems of the countries adhering to the convention. It is defined as the right of performers to prevent fixation and direct broadcasting or communication to the public of their performance without their consent. Once a recording of the performance has been made, the performer's permission is also needed to make copies of that recording. A performer may be entitled to remuneration in respect of broadcasting and other types of communication to the public, public performance and rental of those copies.

Due to the same technological changes, the development of phonograms and cassettes and, more recently, compact discs and their rapid proliferation, has forced considering the protection of producers of phonograms. In addition, there is the increasing use of records and discs by broadcasting organizations; while the use of these by the latter provides publicity for the phonograms and for their producers, these also have, in turn, become an essential ingredient of the daily programs of broadcasting organizations.

Consequently, just as the performers were seeking their own protection, the producers of phonograms began to pursue the case of their protection against unauthorized duplication of their phonograms, as also for remuneration for the use of phonograms for purposes of broadcasting or other forms of communication to the public. Their interest was formalised in the Rome Convention and is implemented by those countries that adhered to it. The producers right is defined as the right of producers of phonograms to authorize or prohibit reproduction of their phonograms and the import and distribution of unauthorized duplicates thereof.

The term "producer of phonograms" denotes a person or legal entity that first fixes the sounds of a performance or other sounds. A phonogram is any exclusively aural fixation of sounds of a performance or of other sounds. A duplicate of a phonogram is any article containing sounds taken directly or indirectly from a phonogram and which embodies all or a substantial part of the sounds fixed in that phonogram. For instance, gramophone records, magnetophone cassettes and compact discs are duplicates of a phonogram.

Finally, there were the interests of broadcasting organizations as regards their individually composed programs. The broadcasting organizations required their own protection for these as well as against retransmission of their own programs by other similar organizations.

The Rome Convention established the broadcasters right as the right of broadcasting organizations to authorize or prohibit re-broadcasting, fixation and reproduction of their broadcasts.

Broadcasting is usually understood as meaning telecommunication of sounds and/or images by means of radio waves for reception by the public at large. A broadcast is any program transmitted by broadcasting, in other words, transmitted by any wireless means, including satellite transmissions, for public reception of sounds and of images and sounds.

Communication to the public by wire is generally understood as meaning the transmission of a work, performance, phonogram or broadcast by sounds or images through a cable network to receivers not restricted to specific individuals belonging to a private group.

Another notion, that of rebroadcasting, is either simultaneous transmission of a broadcast of a program being received from another source, or a new, deferred broadcast of a formerly recorded program transmitted or received earlier.

Copyright does not continue indefinitely. The law provides for a period of time, a duration, during which the rights of the copyright owner exist. This period begins with the creation of the work and it continues until some time after the death of the author. The purpose of this provision in the law is to enable the author's successors to have economic benefits after the author's death. It also safeguards the investments made in the production and dissemination of works.

In countries that are party to the Berne Convention, and in many other countries, the duration of copyright provided for by national law is the life of the author and not less than 50 years after the death of the author. In recent years, a tendency has emerged towards lengthening the term of protection.

In the European Union this period has been harmonised to 70 year after the death of the author. In the United States of America, in response to lobbying by major media companies, the U.S. Congress routinely extends copyright protection to works, as the copyrights are about to expire:

The second limitation or exception to be examined is a geographical limitation. The owner of the copyright in a work is protected by the law of a country against acts restricted by copyright done in that country. For protection against such acts done in another country, the rights holder must refer to the law of that other country. If both countries are members of one of the international conventions on copyright, the practical problems arising from this geographical limitation are very much eased.

Certain end-user acts normally restricted by copyright may, in circumstances specified in the law, can be done without the authorization of the copyright owner. These exceptions to copyright should be considered as end-user privileges and not rights. However, some of them are referred to as rights, e.g. the right to quote.

Moreover, these exceptions do not mean that the exceptional usage is always free. Some of these exceptions allow use of the content without authorisation but require the user to pay compensation. For instance, in some countries, there are levies on digital recording equipment and media.

These are the main rights and usages derived from copyright exceptions:

In any case, these exceptions must comply with the Berne three-step test set of constraints on the limitations and exceptions to exclusive rights under national copyright:

“Members shall confine limitations and exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the rights holder”.

In some countries, works are excluded from protection if they are not fixed in some material form. Moreover, in some legal systems, the texts of laws and of decisions of courts and administrative bodies are excluded from copyright protection. It is to be noted that in some other countries such official texts are not excluded from copyright protection; the government is the owner of copyright in such works, and exercises those rights in accordance with the public interest.

The laws of some countries permit the broadcasting of protected works without authorization, provided that fair remuneration is paid to the owner of copyright. This system, under which a right to remuneration can be substituted for the exclusive right to authorize a particular act, is frequently called a system of "compulsory licenses". Such licenses are called "compulsory" because they result from the operation of law and not from the exercise of the exclusive right of the copyright owner to authorize particular acts.

The remunerations resulting from compulsory licenses are usually collected by collective management organisations. These organisations license use of works and other subject matter that are protected by copyright and related rights whenever it is impractical for right owners to act individually. There are several international non-governmental organizations that link together national collective management organizations.

The international protection of copyright and related rights is performed through a set of treaties managed by the WIPO. They are accessible from the WIPO's Web page, http://www.wipo.org.

There are treaties for the protection of copyright:

There are also treaties for the protection of related rights: